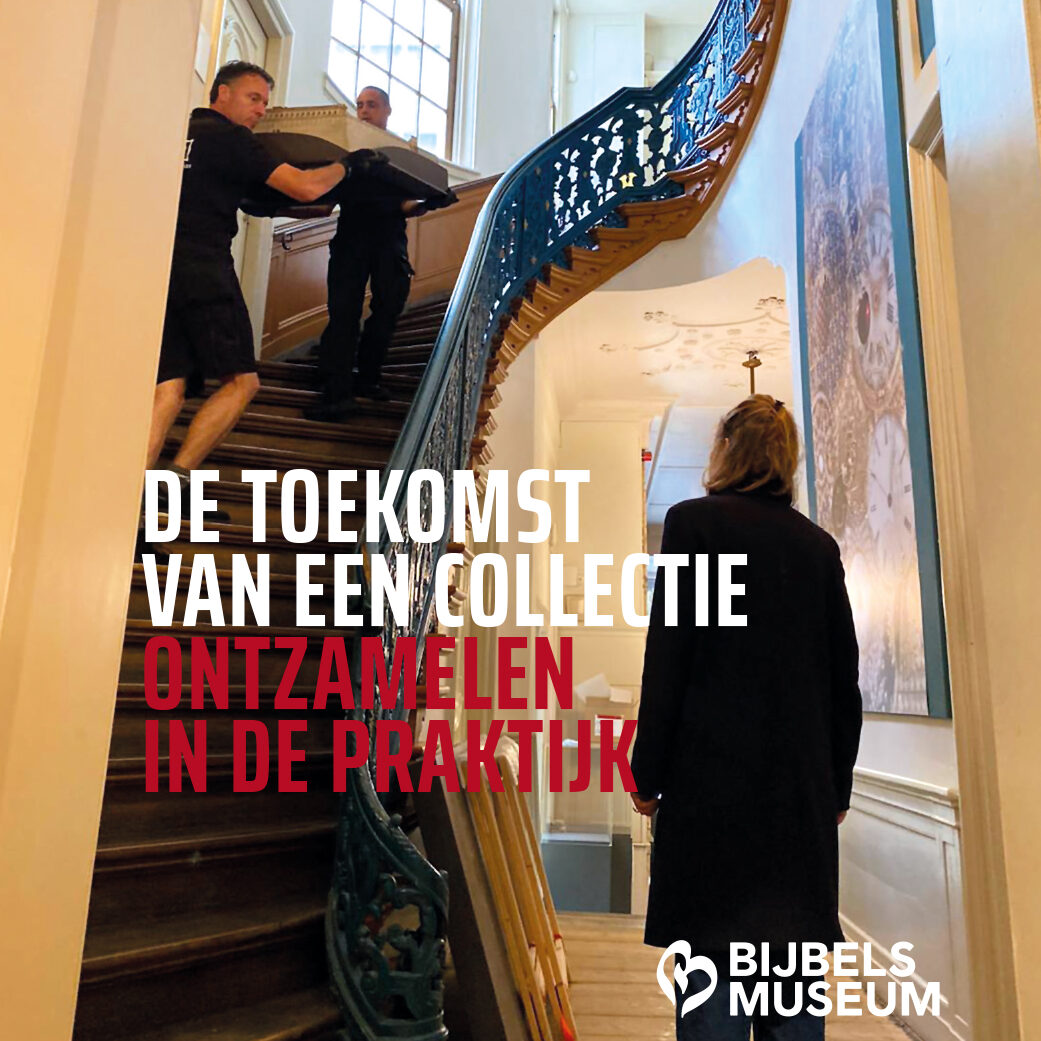

Why and how we deaccessioned our collection – a summary

In August 2016, the Biblical Museum in Amsterdam was informed that the long-term municipal government subsidy would cease in 2017. To cope with this financial blow, the museum proceeded to manage its organisation to be as cost-efficient and effective as possible. In order to reach a wider and more diverse audience, it shifted its focus to travelling exhibitions of contemporary art commissioned by the museum or on loan. For this purpose, it was no longer necessary to hold on to the historical museum collection. In May 2017, the board decided to deaccession its entire collection. As soon as this new course bore fruit, another drastic decision followed a few years later. The museum left its exhibition venue mid-2020, moved into a much smaller office space elsewhere in the city and started to produce travelling exhibitions from there.

Deaccession: Ethical Code and Guidelines

As an officially registered museum, the Biblical Museum had to comply with the Ethical Code for Museums and the Guidelines for the Deaccessioning of Museum Objects (LAMO 2016). This may sound simpler than it actually was. The number of objects was estimated at 30,000, divided into nine sub-collections. Only a small part of the collection was registered and photographed in the digital collection management system and the origin and legal status of many objects was unclear. With the departure of the only curator, who left for a position in another museum by mid-2019, vital knowledge of the collections and an important network left the organisation.

Assessment

In October 2017, the museum asked Tessa Luger, a specialist in the field of collection assessment at the Cultural Heritage Agency (RCE), to manage the first part of the process, the significance assessment of the collection. The curator wrote a new collection policy plan including an inventory of the many-fold components of the collection. At the same time, the director developed a project plan for the deaccessioning process. This described why and how the collection should be relocated and repurposed, and included planning and budget. Further research was required into how to organise this process, how much time was needed and how to estimate the costs of such an extensive deaccessioning project?

Meanwhile, the marketing and communication manager drew up a communication strategy and implementation plan. Transparent and open were the key words. The Biblical Museum opted for a personal approach and informed its key partners early on in the process. For the assessment of the sub-collections and objects, the museum appointed an expert group in the field of the history of Protestantism in the Netherlands. These experts would meet six times for half a day over a period of eighteen months. The significance assessment process was completed by May 2019.

Implementation

In the summer of 2019, the implementation phase started under the leadership of a project manager with the support of two museum collection assistants. The deaccessioning team divided the objects into files, similar to lots at an art auction. For each file, necessary information was collected for publication on the website of the national deaccessioning database (ADB). Every museum in the Netherlands can check this portal for objects or collections that are being disposed of and submit their expression of interest. The portal is also accessible to private individuals. In August 2019, the Biblical Museum placed its first file on the ADB as a pilot project. A total of 105 files followed in a year’s time.

Despite the thorough preparation, new ethical and practical dilemmas regularly arose throughout the process. What do we actually mean by collection? How to decide who gets what? What to do with objects worthy of protection for which there was no museum interest? And how do we deal with donations and acquisitions by living artists? All along, the team was able to find acceptable solutions.

Relocation

Together with museum partners, donors, artists and volunteers, the Biblical Museum sought for the best destination for objects and sub-collections. Since there were initially no responses to the announcements on the ADB, the museum started actively to inform its colleagues of the intended disposals. In some cases, the Biblical Museum deliberately deviated from the official deaccessioning guidelines to ensure the best possible destination for the objects. A large part of the collection was relocated to fellow museums and thus preserved for the National Collection of the Netherlands. The remainder was given a new function with the help of external partners. A very small part was destroyed.

Sharing insights and experiences

In The Future of a Collection. Deaccessioning in Practice, Carolien Croon, director of the Biblical Museum, and co-author Tessa Luger have described the entire deaccessioning process. From the initial decision to dispose of the collection to the handover (and quite surprisingly, the return of some) of the last objects. In eight chapters, twelve interviews with stakeholders and eleven case studies, the authors sketch a picture of the organisational, legal and practical implications. The authors discuss the challenges and sensitivities that are inextricably linked to being forced to dismantle. Former curator Hermine Pool describes in her account of the museum’s history the many developments and changes of direction it has undergone in the course of time.

With this (Dutch only, unfortunately) publication, the Biblical Museum wishes to share its considerations, insights and experiences with museum professionals and heritage students and thus contribute to the further development and improvement of the professional guidelines for deaccessioning museum objects.

2022, Amsterdam